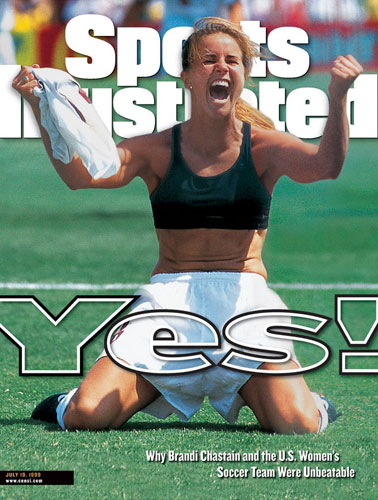

When Brandi Chastain scored the winning penalty shot and took off her shirt to reveal her sports bra time seemed to stand still for soccer fans. In this victorious moment, Chastain revealed her body (her muscles) in a non-sexual manner. For a short window of time people cared about this event enough to write controversial articles, conduct interviews, and put it on the cover of Sports Illustrated. Regarding this week’s readings, the innovations, politics, and controversies surrounding and leading up to this climactic event seem to be a great space to explore the methods Jasbir Purar discusses in her essay “I Would Rather Be a Cyborg than Goddess’: Intersectionality, Assemblage, and Affective Politics” (2011).

Jasbir Puar is an Associate Professor of Women’s and Gender Studies at Rutger’s University. Her essay “I Would Rather Be a Cyborg than Goddess’: Intersectionality, Assemblage, and Affective Politics” bridges the gap between the proclaimed encompassing methods of intersectionality (put forth by Kimberlé Crenshaw) and assemblage (put forth by Donna Haraway) ultimately argues for the appropriation of both feminist methods within academia.

Jasbir Puar is an Associate Professor of Women’s and Gender Studies at Rutger’s University. Her essay “I Would Rather Be a Cyborg than Goddess’: Intersectionality, Assemblage, and Affective Politics” bridges the gap between the proclaimed encompassing methods of intersectionality (put forth by Kimberlé Crenshaw) and assemblage (put forth by Donna Haraway) ultimately argues for the appropriation of both feminist methods within academia.

To begin, Puar understands the theory of intersectionality by stating that “all identities are lived and experienced as intersectional—in such a way that identity categories themselves are cut through and unstable—and that all subjects are intersectional whether or not they recognize themselves as such…intersectionality always produces an Other, and that Other is always a Woman of Color (WOC), who must invariably be shown to be resistant, subversive, or articulating a grievance.”

If we conceptualize intersectionality as a tool (a method) to understand racial difference founded on the principal of inclusion than, as Puar points out, why has intersectionality singled out WOC and supposes the title or crowning feminist method within Women’s Studies Departments. This is problematic for several reasons, the most obvious of which is the fact that intersectionality is understood by Crenshaw “as an event” rather than a static method or supplemental “tool.”

Intersectionality is a practice, a performance, and even an “accidental” construction of identity. According to Crenshaw and Puar, the flow of discrimination (or perhaps cultural constructs) is interrupted when an event takes place, which temporarily stops this flow. This collision opens up a new space-time, or what Michael Taussig describes as the “time of the now,” when the collision of ideologies, or in the case of the 1991 FIFA World Cup the destruction of traditional gender norms, stops the flow temporarily, to reveal the inner (most-times ugly, racist, and sexist inner structures). During this time new information, data, and material fractions are released and pieced together, investigated, and more-or-less determined to be one thing or another. What if the collision produces something new? This investigation seems to be crucial part of the performance of interactivity, but also perhaps the process of becoming. If we understand identity as fluid is it possible for subjects in an accident, particles in a collider, or two methods of thought to simply walk away unaffected after they have been hurled around at high speeds and crashed into one another? Doesn’t intersectionality need to be crashed into in order to prove itself?

I might be thinking to literally here, but if our existence—our identities—are dissolved until all that is left is a cyborg (a body that has come into being through an amalgamation of organic and technologic material), which is intrinsically “unstable” how is it possible to categorize itself as something other? In Purar’s opinion, Haraway’s assemblage does not avoid categorization, but “a cyborg actually inhabits an intersection.” Perhaps, the cyborg, as assemblage, must live inside the intersection, or the now time, at all times in order to avoid the verdict? Puar thinks of assemblage not in a static body, but as “a pattern of relations.” Puar states that “[u]nlike Crenshaw, the focus here is not on whether there is a crime taking place, nor determining who is at fault, but rather asking what are the affective conditions necessary for the event-space to unfold?”

In Haraway’s essay “Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Plantationocene, Chthulucene: Making Kin” she describes the future as over-crowded where the best option is to “make kin not babies.” In this world I don’t think it’s possible to be a “goddess.” Cyborg is the only option. Haraway states that “[m]y purpose is to make “kin” mean something other/more than entities tied by ancestry or genealogy.” Here she already uses the term, “other” which is problematic. Moreover, she qualifies this statement by stating that “all earthlings are kin in the deepest sense.” Puar’s point that intersectionality and assemblage are not mutually exclusive ( and perhaps need to crash into one another), would be useful to consider. Specifically, the intersectional space of assemblage, since the friction that’s created by rubbing these methods together seem to be constrained by time.

At this time, I would like to think about the sports bra as an important piece of feminist technology. Fortunately, populating my pod-cast feed this week was a piece titled “The Athletic Brassiere” produced by Phoebe Flanigan for 99% Invisible. This episode chronicles the invention and evolution of the sports bra, originally called the “Jock Bra” by its inventors Lisa Lindahl and Polly Smith in 1977. Before Lindahl and Smith re-imagined the brassiere to function more like a jock strap to offer more support, women were discouraged from participating in sports because the bras at the time were uncomfortable and constrictive. The sports bra, as a feminist piece of cyborg technology, encouraged women to participate in sports, introduced more women’s sporting events, and eventually led to a crash or climax in 1999 at the FIFA Women’s World Cup final. Later, this space for change, or now-time, was reopened when Serena Williams refused to wear the traditional white at Wimbledon in 2012 opting for untraditional cuts and bold colors.

If we read assemblage as “a pattern of relations” and combine an intersectional approach we can begin to effectively piece this narrative together. I agree with Puar, that including both methods (and perhaps more) is crucial, not only in academia, but also into practices outside of the university.

References:

Haraway, Donna (1991) “A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century” In Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature, 149–81. New York: Routledge.

Haraway, Donna (2015) “Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Plantationocene, Chthulucene: Making Kin” Environmental Humanities, vol. 6, pp. 159-165.

Puar, Jasbir (August 2011) “‘I Would Rather Be a Cyborg than a Goddess’: Intersectionality, Assemblage, and Affective Politics.” Transversal.

Taussig, Michael. “Iconoclasm Dictionary” was originally presented as a keynote address for “Iconoclasm: The Breaking and Making of Images” conference, University of Toronto, 17–19 March 2011.

Your description of the sports bra as a cyborg technology was so interesting! I also was intrigued by the interrogation of temporality as it relates to these iconic sports moments you mentioned. I also wonder, if we use the image of the intersection collision in which space-time is opened up, what role context plays in the “size/weight” of the vehicle colliding? I was reading an introduction to a book by Roderick Ferguson and Grace Kyungwon Hong for another class called “Strange Affinities” which described how contextualization/time adjust experience/legibility/visibility of specific aspects of identity–as they collide, how does context change the shape and weight of specific colliders?

LikeLike

I want to push the sports bra as cyborg feminist technology even further because I like it so much. Thinking about the image of it and how it was sexualized, or seen as inappropriate to reveal. The marketing language of sports bra as “support” and “jock” i.e. for utility, vs. bras that are for showing- what does it mean when bras are marketed to be seen, rather than unseen? Great object to use for this analysis!

LikeLike

Your point about the sports bra being a feminist piece of cyborg technology is very interesting. The tool, in general, serves to expand or augment human “natural” capacity. Consequently, we might see human nature as fundamentally cyborgian; that is, that our existence is always already marked by the use of something external. What is interesting in this is that the tool comes to act like a prosthesis precisely because tools have expanded conceptions of the body in terms of ability to a point where we rely upon them. I see two implications in this. First, our bodies have never actually been distinct as such. Instead, there has never been a true isomorphism between “meat” (the biological matter) and “body” (the cultural unit). Second, and relatedly, it seems that the forced isomorphism between the two can only exist within a particular ontological paradigm. In this way, then, Haraway’s cyborgian terminology ironically conceals the historical reach of her point. I wonder, therefore, if we can consider a dissolution of the problematic of distinctness and interconnectedness in the past as a new means of critical history.

LikeLike

Your thinking about the sports bra as a piece of cyborg technology is great. I immediately wanted to know more and started to think about how other gendered articles of clothing or objects we have around the house can be thought of as cyborgian. I think we can go all the way down the level of materials that are used in the bra to consider how it is a cyborg technology. Sportswear today commonly touts qualities like moisture wicking, thermal insulation, cooling barrier, etc. that augment our natural capacity as athletes.

LikeLike