On January 6, 2011, Aaron Swartz – a research fellow at Harvard University, as well as a computer programmer, political organizer and Internet hacktivist – was arrested for breaking-and-entering charges, regarding the systematic downloading of academic journal articles from JSTOR. He was charged with 2 counts of wire fraud and 11 violations of the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act of 1986. These charges could have led to a cumulative maximum penalty of $1 million in fines as well as 35 years in prison, asset forfeiture, restitution and supervised release. In 2013, Swartz committed suicide, and the case was consequently dismissed. In 2017, Alexandra Elbakyan, founder of academic research pirate site Sci-Hub – which allows you to download research papers, even when they hide behind publishers’ paywalls, challenging a pay-to-play mentality that has come to plague scholarship – has come under fire for alleged mass copyright infringement and counterfeiting: in June, Elsevier won a $15m judgement against Sci-Hub and the site is also facing legal action from the American Chemical Society. Sci-Hub has been shut down in Russia.

These instances demonstrate the extent to which academic publishers will go to protect their profit-driven databases in the face of a struggle for equal access to scientific information. Initiatives such as the 2007 Overprice Tags, organized by Benjamin Mako Hill – wherein MIT students placed overprice tags on the 100 most expensive journals in their library –, emphasize the sobering reality of the subscription model in scientific publishing. Hill believes that “for something as important as basic research and scientific knowledge, [lack of access] becomes profoundly unfair”. In addition, many sustainable platforms for scholarly communications have sprung from the Open Access movement in the form of open libraries and commons, such as the Science Commons and the Open Library of Humanities, which facilitate more efficient web-enabled scientific research.

Nelson Pavlosky, co-founder of Students for Free Culture, states: “I’m a big fan of DIY culture […] I like giving people the tools and information they need to figure things out for themselves and get things done, so that they don’t have to rely entirely on some class of experts to think and act for them.” A contemporary iteration of such DIY praxis is the Hashtag Syllabus, Twitter-fueled crowd-sourced reading lists that assemble critical intellectual resources and promote collective study on various subjects, such as racism, immigration, islamophobia, rape culture and prison abolition. Pertaining to access as it touches systemic deficiency of certain contents – namely, social, historical and academic erasure and negligence towards some areas of knowledge – , the syllabi are intended to, as Lisa A. Monroe articulates, “arm educators and parents with resources to discuss current social conflicts, to provide historical contexts […] and to empower people in and outside of the classroom to take informed action however they may choose.” In turn, Chad Williams emphasizes the importance of canon formation in the development of any intellectual or literary tradition, commending the #CharlestonSyllabus for containing texts, novels, poems, films, songs and primary source documents that are foundational to the study of the black experience and the meaning of race in modern history:

The #CharlestonSyllabus reflects not only the creation of African American intellectual history but engagement in its practice as well. The act of soliciting and organizing a crowd-sourced collection of resources carries on the work of black bibliophiles like Arturo Schomburg, Edward C. Williams, and John E. Bruce. If alive today, these forbearers would no doubt marshal all the creative tools at their disposal—including social media—to further institutionalize the canon of black studies and find ways to disseminate information to as broad an audience as possible. The hashtag, if mobilized conscientiously, can function as a bibliographic marker and tool for historical literacy. This approach is also inherently democratic, reaffirming an ethos of shared communal knowledge production that is at the core of the black intellectual tradition. Anyone, regardless of training or credentials, can offer a suggested addition to the #CharlestonSyllabus, and anyone, irrespective of educational level or proficiency in African American studies, can have access to the list of resources.

Hashtag Syllabi form a community of people committed to critical thinking, truth-telling and social transformation, modeled after communal thought and self-education. They place current events in a broader historical, political, economic, and social context, promoting critical discussion and debate. The syllabi operate independently – relying on social media to expand and flourish (they are, however, moderated, so also subject to biases) – and are widely accessible, providing tools for web-based research as well as prompting active learning and activism.

Participatory practices and learning as they relate to technology can also be observed in contemporary art, for example. Artist Ai Weiwei recognizes in Twitter an important tool in our perception of reality and establishing our history, with great creative potential:

Twitter is a very interesting medium. It is not one that records the past, but one that forms in the present condition, with real connections to the future. It is so intimate but, at the same time, so broadly connects us to others. Humans have never had this in our history. By changing the way we communicate, it changes our understanding of ourselves and others. That gives a new definition to our society, to democracy, civil rights, and humanity as well.

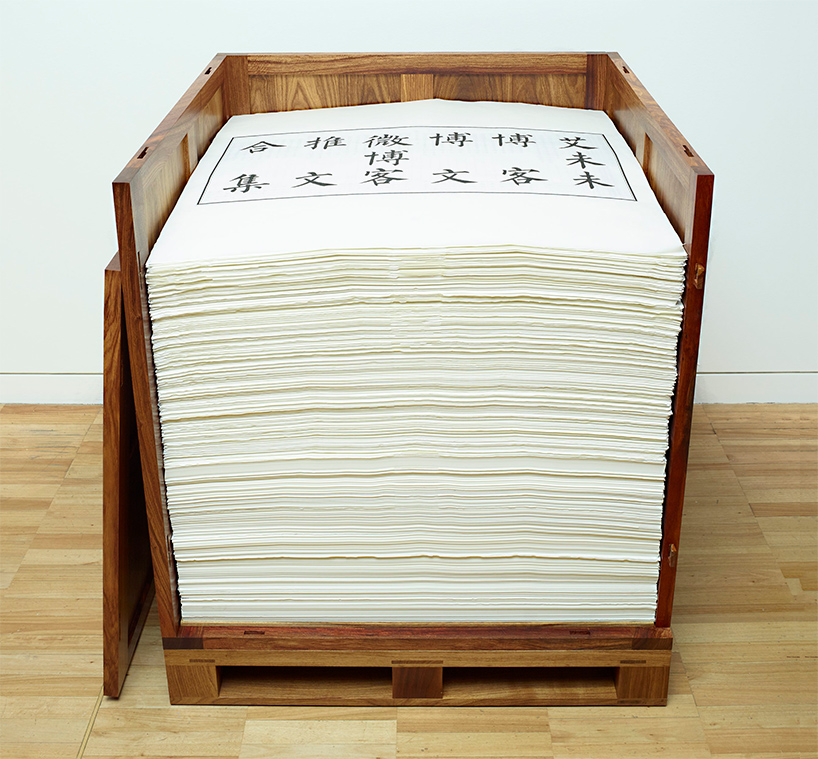

Ai was banned from Chinese Twitter (Sina Weibo) and his blog was shut down by Chinese authorities. His 2015 artwork An Archive was a collaboration with traditional Chinese printmakers consisting of 6,830 painstakingly printed pages of rice paper, chronicling his social media commentary over 8 years (2005-2013), in Mandarin. The accumulation of sheets are stacked in a traditional huali wood box.

Ai Weiwei’s An Archive (Azzarello, 2015).

In 1996, Lynn Sowder (apud Lacy, 1996: 31), independent curator, asserted that “We need to find ways not to educate audiences for art but to build structures that share the power inherent in making culture with as many people as possible”, and asked “How can we change the disposition of exclusiveness that lies at the heart of cultural life in the United States?” Technology, the internet, and social media might hold material possibilities to instill change in the art world and society at large, through collaboration, empowerment and autonomy.

The idea of an audience is crumbling as previously elite roles and tools are made available to the public. It is becoming increasingly possible to construct one’s own classroom, syllabus, curriculum, one’s own exhibit, study group, cinema, workshop, laboratory, etc, towards a horizontal, reparative, representative, and practical education. Brushing history against the grain, as Benjamin (1940) puts it: refusing to identify ourselves with winners and conquerors and glimpsing the barbarism contained in culture and the transmission of culture. This implies the de-identification with a historical subject that is masculine, in addition to “re-functionalizing” (Benjamin, 1987: 127) the cultural goods that all founding structures of contemporary society helped to erect and keep segregated. It is a complex task for it intends to dispute the tradition against the conformism that aims to dominate it, but we are nothing if not persevering.

Works Cited

United States of America v. Aaron Swartz (2012).

Geltner, G. (2017). The Future Of Academic Publishing Beyond Sci-Hub.

Cragg, Oliver (2017). Sci-Hub facing $4.8m piracy payout as site shut down in Russia over ‘liberal opposition’.

Page, Benedicte (2017). Elbakyan pulls Sci-Hub from Russia.

Benjamin Mako Hill (2007). Overprice Tags.

SPARC (2017). Agents of Change – Student Activists for open access.

Science Commons (2017). Science Commons: Making the Web Work for Science.

Monroe, Lisa A. (24 October 2016) “Making the American Syllabus: Hashtag Syllabi in Historical Perspective” in Black Perspectives Journal.

Williams, Chad (2015). #CharlestonSyllabus and the Work of African American History.

Saccardo, Nadia (2015). [Exclusive] Ai Weiwei says Twitter is Art.

Azzarello, Nina (2015). ai weiwei archive includes 6,830 rice paper sheets of printed tweets.

Lacy, Suzanne (1996). Cultural Pilgrimages and Metaphoric Journeys In Lacy, Suzanne (org.). Mapping the Terrain: New Genre Public Art. Seattle: Bay Press.

Benjamin, Walter (1940). On the Concept of History.

Benjamin, Walter (1987). Magia e técnica, arte e política: ensaios sobre literatura e história da cultura. São Paulo: Brasiliense.

*Featured image: “More Schools, Less Prisons”. In 2015, Brazilian High School students occupied the 9 de Julho Ave. in protest against public school reorganization in the state of São Paulo, one event of a series of protests and occupations. Their mobilization was largely organized and publicized through the Internet, fostering similar movements in many different regions of the country.

Your opening examples of the lengths to which institutions/publishers will go to keep information from being freely available are extremely striking (and a great attention grabber for this post!). As a personal connection, my brother is in medical school currently and throughout his undergraduate and medical education has accessed blocked publications through a site which apparently must continually change the characters after the “.” in its URL because previous sites are being shut down so quickly. The site’s URL has ended in “.io,” “.oa,” and on and on with different vowel iterations so much that my brother ends up trying out different ones until he finally accesses the site. Which, also, is wild since he is a member of an institution that you would think would provide him access to medical research. Even inside of fields, the capitalistic hoarding of knowledge in pursuit of profit is keeping folks from collaborating and learning.

LikeLike

Thank you for bringing up the topic of access and censorship in relation to social media and art (in the case of Ai Weiwei). The artwork “An Archive” (2015) is so powerful because of its absurdity. Ai complicates ideas about censorship, information and labor by emphasizing the skill, technique, and required time of the paper maker, box maker, and printer. Ai’s views are optimistic about the internet, which is not only reflected in the quote you included, but also in the wit of this piece–that there is only one essentially inaccessible “archive” consisting of rice paper printed Tweets. Here the action of the Chinese government to ban Ai is the moment to be remembered and the prints are the anti-monument to that political action.

LikeLike

I greatly enjoyed your post, particularly your references to Benjamin and your approach to subjectivity as a masculinized cultural construct. I would also tend to agree with your interpretation of the internet as having the potential to break down earlier hierarchies of production. One question, however, is to what extent new hierarchies of knowledge/information generation borrow their trappings from earlier (modernist) models. In other words, to what degree is content creation actually equitable when we consider the basic and necessary material trappings? In any case, I think it is worth discussing how to actualize your points in praxis.

LikeLike

Thank you for bringing the question of paywalls and access in scholarly publishing to our conversation! What stood out to me, reflecting on my own experiences with paywalls in academia and in the art world, was that–exactly to your point–often even those who work in a particular field find themselves in a tight spot with regard to available materials. The curators at the art institution I worked for, who were in the process of writing scholarly articles, consistently found themselves without access to the sources they needed. They were using the local library when it came down to it because they were not granted access to databases like JSTOR.

LikeLike

The way your argument moves from the gated-community of publisher paywalls and JSTOR into the public domain of social media works really well in trying to conceptualize the potential of a #Syllabus. The example of Ai Weiwei is a helpful model for thinking of censorship in conjunction with the hope that the content of a #Syllabus can be distributed to the widest audience possible. Ultimately, as you have stated, communal models of education are necessary in order to realize and achieve social change, but channels of distribution must continue to evolve with the forces that aim to suppress it.

LikeLike

Response to leticiacobra

The story of Aaron Swartz makes me worry for and disdain academia and the institution (and frankly capitalism, too tbh) for not only putting a price tag on knowledge and information but also for having procedures with detrimental outcomes penalizing those seeking knowledge.

These are the hoops one jumps through to get as much information on a topic as they can, else risk the opportunity for others to dismiss their work as haphazard, incomplete, or etc. because of a missing article that required a fee to read.

Others commenting also feel strongly about paywalls in academia. Have you disliked the UC library system so much that you went back to your undergrad’s library system? I did wth Illinois. I noticed that some schools have access to some journals while others don’t. How is this helping the academic landscape? I just don’t get it. I applaud those make it their mission to get out research to the masses by any means necessary.

LikeLike

I really enjoyed reading your post, your connections to profit-based academic journals and contemporary art expanded my understanding of Hashtag Syllabi as a DIY project and its connection to censorship. I believe that Hashtag Syllabi, and their social justice fights, have to include an effort towards open source knowledge. As you said, the limited access and high cost of scientific articles functions against equal learning opportunities. Since the syllabi are meant to bring marginalized voices to the forefront, I think it’s utterly important for them to also make sure that marginalized groups are able to hear them. That is in part why I really like the #StandingRockSyllabus since it not only talked that talk, but also walked the walk of democratizing knowledge and fighting censorship.

LikeLike

I really enjoy the broader context you build for the #syllabi, especially as it relates to the art world and for alt-academics. I attended a panel on “Alt-Academia” at UCSB last year, and one of the participants talked about how once she finally gave up on finding an academic job, she had an intense grieving process. As part of this monologue, I remember distinctly that she really struggled with a dearth of resources, including access to journals, once she left grad school. Since we’re part of the academy right now, it’s easy for us to talk about access in terms of “other” populations, but the reality is that within the next 5 years, many of us will probably be a part of those populations. In a way, these interrogations regarding access aren’t just for others, they’re also for our future selves.

I’m also interested in your inclusion of Benjamin here. I’m not sure that I understand it and would love to unpack this more in class today!

LikeLike